It all started with a boy on a train.

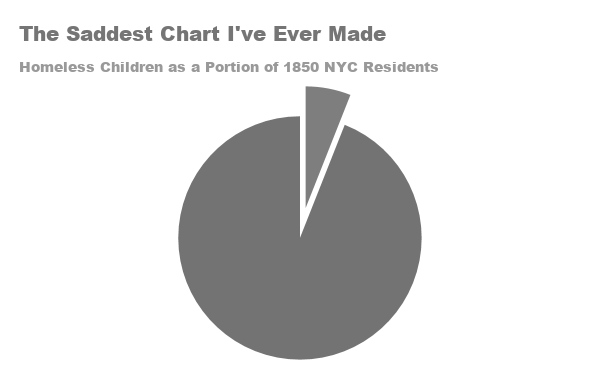

Back in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, urban cities along the eastern seaboard had a problem. In 1850, New York City had a population of 500,000 people. Of that, up to 30,000 were homeless children.

In 1854, the newly formed Children’s Aid Society saw that while New York City had too many kids, many areas in rural America would welcome additional children to help on their farms. Their solution? Put kids on a train and send them westward.

This orphan train would make stops in towns as it traveled across the midwest. Some children would be claimed at each stop, and the others would get back on the train and continue to the next town.

Although adoption had existed prior to this (mostly in terms of indentured servitude), this was the first real “adoption” program of the modern era.

This program is also where we get the term “put up for adoption.” It referred to (quite literally) putting kids up on a stage for display to townsfolk. It was almost like a used car auction, where potential parents would poke and prod the children trying to find their best fit. The plan was for local panels to determine the best families to place orphaned children in, but this didn’t work well in practice. With very little oversight, many children got placed in bad situations and were mistreated by their new families.

The orphan train sounds crazy, because it was. The program lasted from 1854 until 1929, and transported over 200,000 orphaned children from New York to elsewhere in the US.

But we’re specifically interested in one of those orphaned children: Joseph Fuourka, a one year old baby who was loaded on a train headed for Louisiana in 1905.

While many kids were mistreated in their new homes, Joseph was lucky. He got claimed by a priest just south of Lafayette.

Unfortunately, Catholic priests cannot have children (apparently even adopted ones), so Father Johanni Roguet handed over the responsibilities to a local widow named Eliza Aillet.

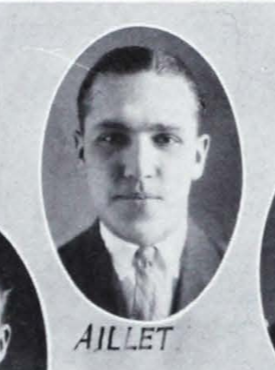

Thus, the baby was renamed Joseph Roguet Aillet.

But you can call him Joe.

Joe Aillet was sent to New Orleans for high school, attending Holy Cross School.

Interestingly, Holy Cross only existed because in 1842, the Archdiocese of New Orleans asked a group named the Congregation of the Holy Cross (fresh off of founding Notre Dame in South Bend) to take over an orphanage. But 30 years later, the need for an orphanage diminished and the group could focus on a new project: a school.

And in 1921, the kid from the orphan train graduated from the school that owed its existence to an orphanage.

Continuing with his Catholic upbringing, Aillet went on to St Edward’s College in Austin, Texas. There, he played in multiple sports, including (if you couldn’t guess it) football.

In an odd twist of fate, Tech has played St Edward’s exactly one time in the history of the universe. And that one time was in 1924 while Aillet was on the team.

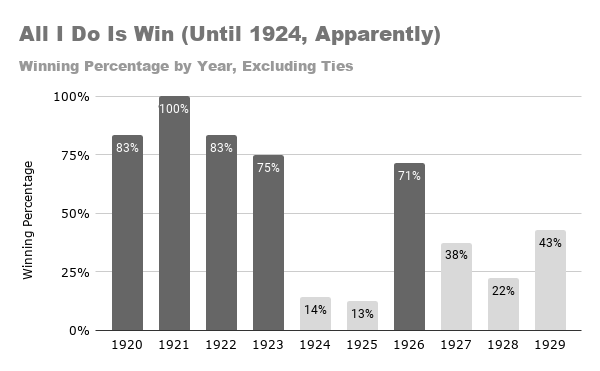

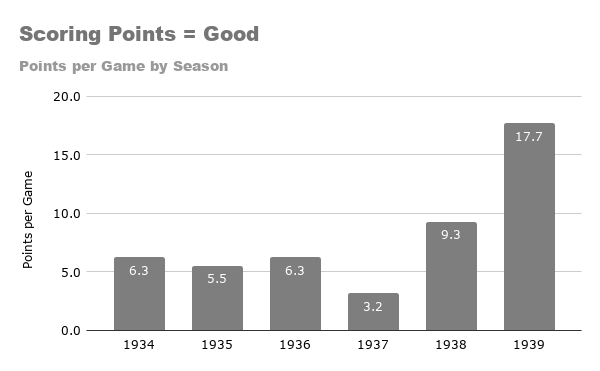

Let’s see that chart from Part I about how Tech performed in the mid to late 20s:

Yeah… the Bulldogs lost the 1924 match to St. Edwards 28-12.

After wrapping up his playing career in Austin, Aillet headed back home to finish up his bachelor’s degree at (unfortunately) Louisiana-Lafayette. Well, at the time, it was known as Southwestern Louisiana Institute. But still, it was definitely not known as “Louisiana”.

While at ULL, Aillet was a student assistant coach for the football team. He was also elected Governor of the Sigma Pi Alpha fraternity in his first and only year attending the school. If that doesn’t scream leadership, I don’t know what does.

(Also, Sigma Pi Alpha doesn’t seem to exist anymore. I’m pretty sure it’s not related to the latina-based sorority that now uses that namesake.)

After leaving ULL, Joe Aillet knew he wanted to coach. He headed up to Haynesville to take over the football duties for Haynesville High School. When Aillet arrived in the Claiborne Parish town, it housed less than 1,000 residents. Ward 3 of Claiborne Parish (which included Haynesville) contained less than 5,000 people.

Despite the setting, Aillet built a team that won three state championships in eight years. At the time, there were no divisions in state athletics (no 5A, 4A, etc.). So Haynesville competed against schools in the state like Jesuit in New Orleans or Byrd in Shreveport for those championships.

His success with limited resources got him noticed by Northwestern State (then called Louisiana Normal).

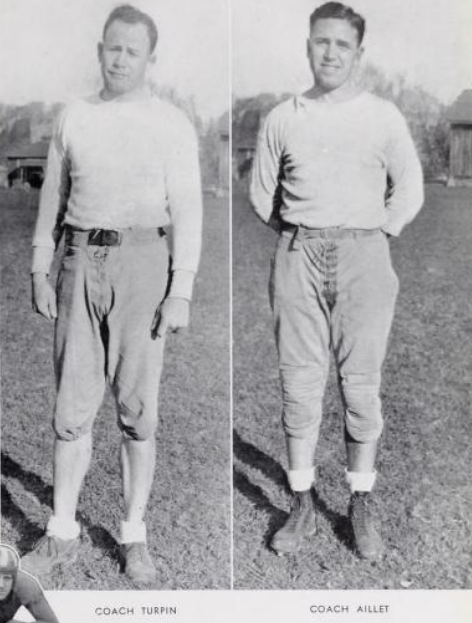

Last post, I mentioned Johnny “Red” Floyd who Middle Tennessee eventually named their stadium after. This time, it’s Larry Turpin who gets mentioned, NSU’s stadium’s namesake.

Showing off your shins was all the rage at the timeTurpin brought Aillet in to Natchitoches to coach offensive backs, while also giving Aillet the opportunity to attend LSU to finish his Master’s degree. Aillet’s first three years in the college ranks provided mixed results, with each season ending up around .500.

But in his fourth season, the team had a breakthrough year by winning the SIAA conference with a perfect record, the first in Northwestern State school history.

Much of that success was due to Aillet’s offense, which scored the most points per game since before his boss (Larry Turpin) was hired.

Of course, some of these points were against Tech, and those are bad pointsA turnaround like that is going to grab some attention. Tech, who had lost to Aillet at three different schools (St. Edward’s, ULL, and NSU) certainly noticed. In 1940, Tech made the move and gave Aillet his first head coaching gig.

The first move Aillet made at Tech was to place academic requirements on scholarship football players. This is normal now, but at the time, as long as you attended the school, you could play on the team. That decision hurt in the short term, as 21 members of the team left.

Despite that, Tech went 6-4 in their first year with Aillet at the helm. After two straight losing seasons, it was good to be on the right side of .500.

More importantly though, the Bulldogs were able to defeat Centenary. While this would probably not be a challenge today (mostly due to the lack of a current football team for Centenary), the Gents ruled North Louisiana in football at the time. Before Aillet, Tech had lost to the Shreveport school in each of the past 19 seasons.

After hiring Aillet, the Bulldogs never lost to them again.

The next year (1941), Tech expanded on their success, taking home a conference championship, their first in 20 years. Oddly enough, Tech ended that year with a worse record than the year before. They beat every conference opponent and lost to (or tied with) every non-conference opponent. But who cares when you got that ‘ship?

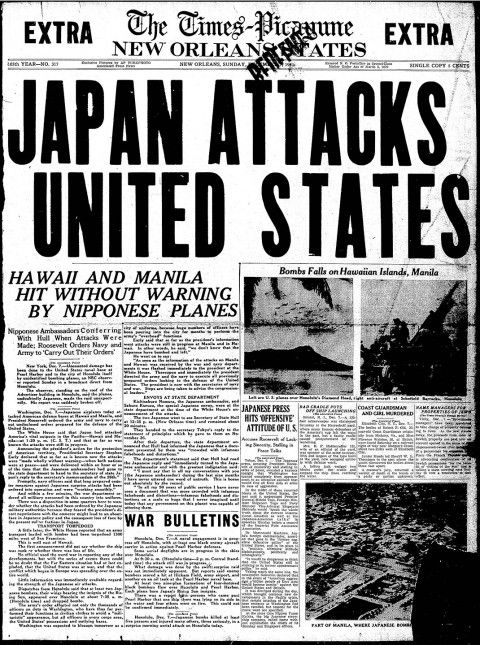

Now we’re getting close to the mid-40s, which means it’s time for another newspaper front page:

WWII: The Prequel to WWIIIWith no football, Tech technically went undefeated in 1943. Aillet returned to coach a team in 1944, but that’s a story for a different post in the Tech Football History Extended Universe™.

Then, in 1945, Tech won another conference title. Two years later, they won yet another.

In 1948, Aillet helped found the Gulf States Conference, and served as its first president. Southern Miss would win the first ever title in the new conference, but Tech followed the next year.

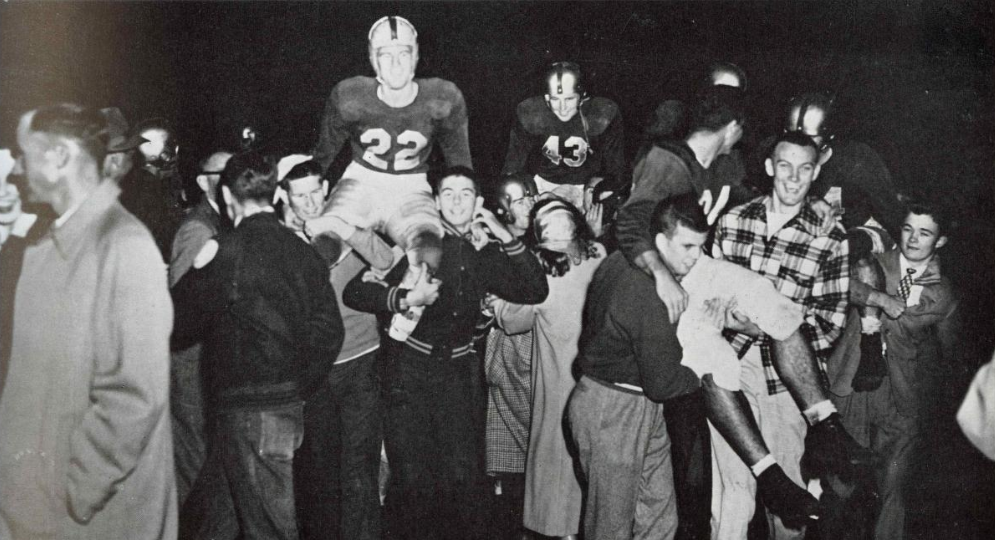

Time to play "Football Celebration or Bar Mitzvah?"By the end of the 1940s, Aillet had been the Tech coach for 10 years (even if only 9 seasons due to the War). In every odd number season that was played, the Bulldogs won a conference championship.

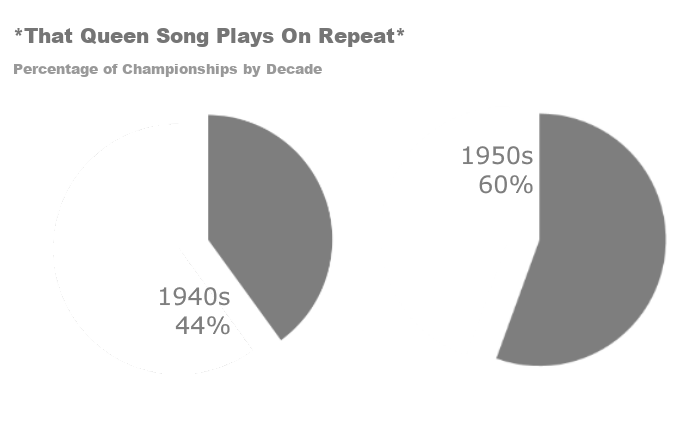

And yet, Aillet’s next decade was even better:

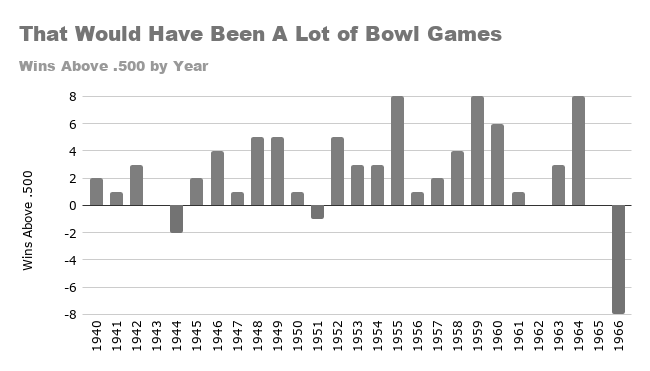

And that’s really how you have to talk about Joe Aillet’s time at Tech: in large swaths of time. Simply put: his teams were consistently good. Excluding the during-war 1944 team and his final year in 1966, Aillet only had one other losing season (1951). Let’s take a look at his year-by-year record:

Aillet’s Bulldogs reached a 9-1 record three times during his coaching career. Each of those three losses were one possession games, and two were by the hands of Mississippi Southern before they moved around the words in their name. The most excruciating of these close losses was in 1955, by a single point.

Luckily, a single point loss never happened again at Tech, right guys?

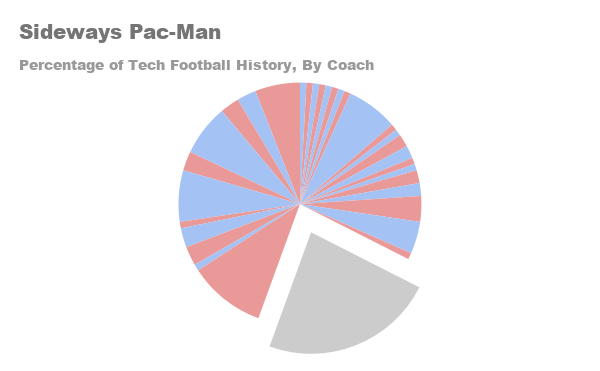

By the end of the 1966 season, Aillet retired from his head coaching duties after a 27 year career. To give an idea of just how much of Tech football history the “Aillet Chunk” is, here a chart with alternating blue/red stripes for each head coach:

Joe did stay on as Athletic Director when he vacated the head coaching position. Until then, the Athletic Director and Head Football Coach positions had usually been held by the same person at the same time. Although he felt like his coaching time was done, he still wanted to oversee Tech’s new athletic complex that was being planned.

It included JC Love Field, the Jim Mize Track Complex, and the football stadium that would later be named for him.

As AD, Aillet also had a pretty big say in his replacement as coach. And he picked one that would go on to build upon Joe’s own success. But we’ll talk about that next time.

Aillet was only able to serve as AD for four years before he was forced to retire by the same thing that killed him months later: cancer.

Joe Aillet wasn’t the first coach at Louisiana Tech, but you would be hard pressed to find someone who wouldn’t call him a founding father.

And on December 28, 1971, Louisiana Tech football was orphaned.